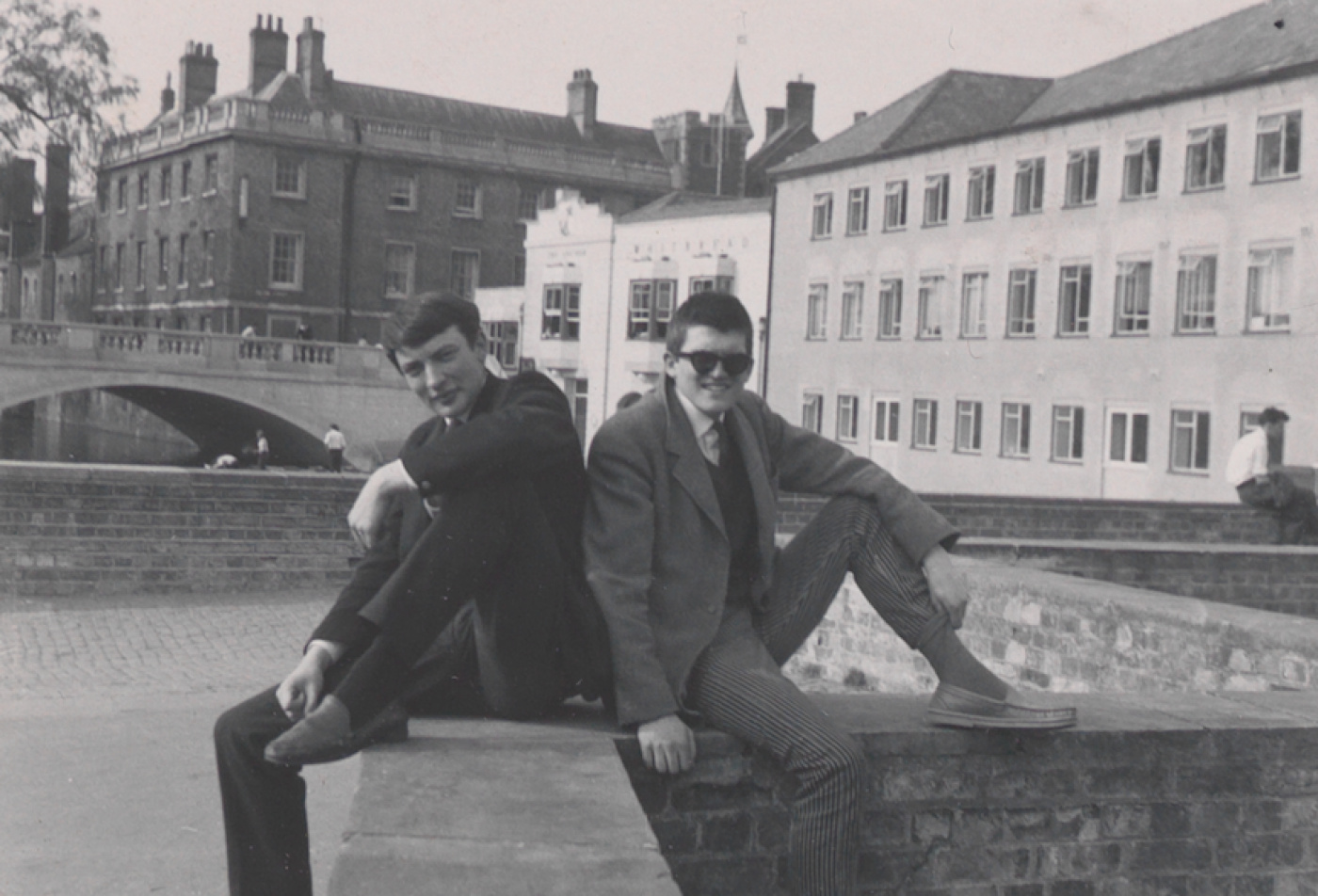

Peers at the RCA

At the Royal College of Art, in addition to R. B. Kitaj, Hockney bonds with fellow students Derek Boshier, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, and Patrick Caulfield. For a spell he experiments with the U.S.-influenced style of abstract expressionism that many of his peers are favoring, but quickly moves on.

I realized there were two groups of students there: a traditional group who simply carried on as they had done in art school, doing still life, life painting, and figure compositions; and then what I had thought of as the more adventurous lively students, the brightest ones, who were more involved in the art of their time. They were doing big abstract expressionist paintings on hardboard.

Young students had realized that American painting was more interesting than French painting. The idea of French painting disappeared really, and American abstract impressionism was the great influence. So I tried my hand at it, I did a few pictures, about twenty on three feet by four feet pieces of hardboard that were based on a kind of mixture of Alan Davie cum Jackson Pollock cum Roger Hilton. And I did them for a while, and then I couldn’t. It was too barren for me.

Pablo Picasso at Tate Gallery

Pablo Picasso’s model becomes crucial for Hockney after he sees a major exhibition of the Spanish artist’s work at Tate Gallery, which is also a remarkable eye-opener for England at large.

In 1960, for a young art student trying to think of modern art, the art of his time, obviously wanting to be involved in it, the opposition to the figure as a subject was very strong. I opposed it too; I thought, this is not the way to go. Yet obviously I was dying to do it, to come to some terms with the figure. Hence the use of words to make the feeling you get from the picture more specific.

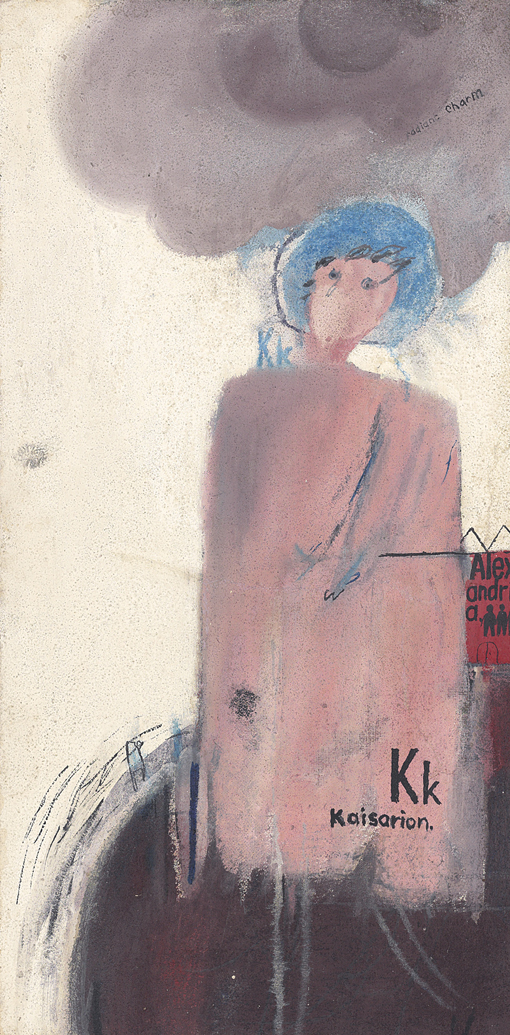

Walt Whitman and the “love” paintings

Hockney’s paintings begin to feature figures not drawn from life but rather largely abstract in form, and accompanied by suggestive, sometimes effusive phrases and statements, for example “I am he that aches with amorous love,” from a poem by Walt Whitman (American, 1819-1892). Hockney is voraciously reading Whitman’s work—it fuels his series of “love” paintings, including the breakthrough work Adhesiveness, which is Hockney’s “first attempt at a double portrait,” by his own reckoning. Adhesiveness borrows its title from Whitman’s term for friendship, with the numbers on each of its two interpenetrating figures based on the poet’s code: 4.8 stands for D.H; and 23.23 for W.W. (Walt Whitman).

Adhesiveness is the first really serious painting I’d done; it is my first painting to begin to have precision.

When you put a word on a painting, it has a similar effect in a way to a figure; it’s a little bit of a human thing .… It’s not just paint.

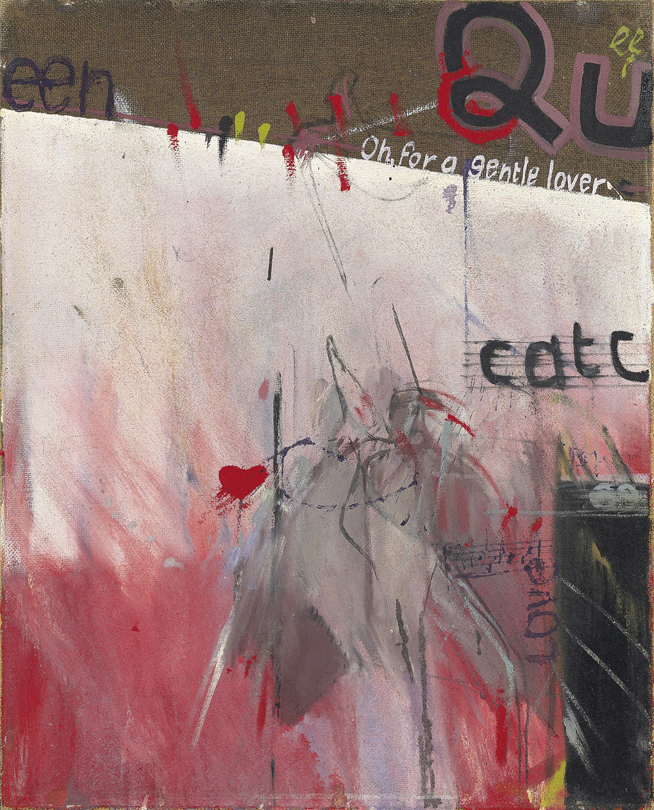

The Third Love Painting

There are lots of ways you can read the title The Third Love Painting. But the painting itself is just an abstraction. It’s very close to abstract expressionism, in a way; there are one or two shapes that rather dominate it and can be interpreted in, I suppose, an ordinary way. But you are forced to look at the painting quite closely because it is covered with lots of graffiti, which makes you go up to it .… If you see a little poem written in the corner of a painting, it will force you to go up and look at it. And then the painting becomes something a little different; it’s not just, as Whistler would say, an arrangement in browns, pinks, and blacks.

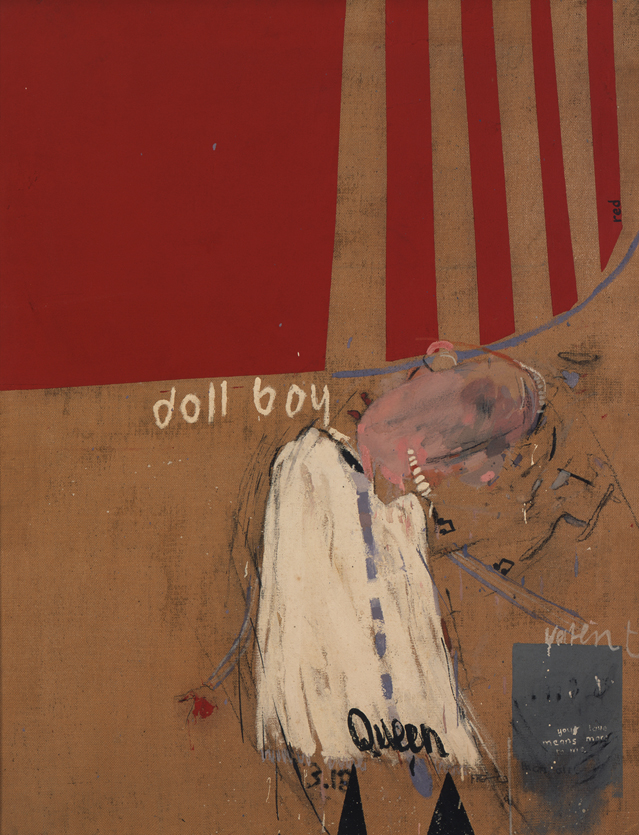

Doll Boy

Hockney’s infatuation with the pop singer Cliff Richard is the impetus for another Love painting, Doll Boy, in which Richard is expressionistically rendered with the word “queen” scrawled across his lower body.

I used to cut out photographs of Cliff Richard from newspapers and magazines and stick them up around my little cubicle in the Royal College of Art, partly because other people used to stick up girl pin-ups .… He had a song in which the words were, "She’s a real live walking talking living doll," and he sang it rather sexily. The title of the painting is based on that line. He’s referring to some girl, so I changed it to boy.

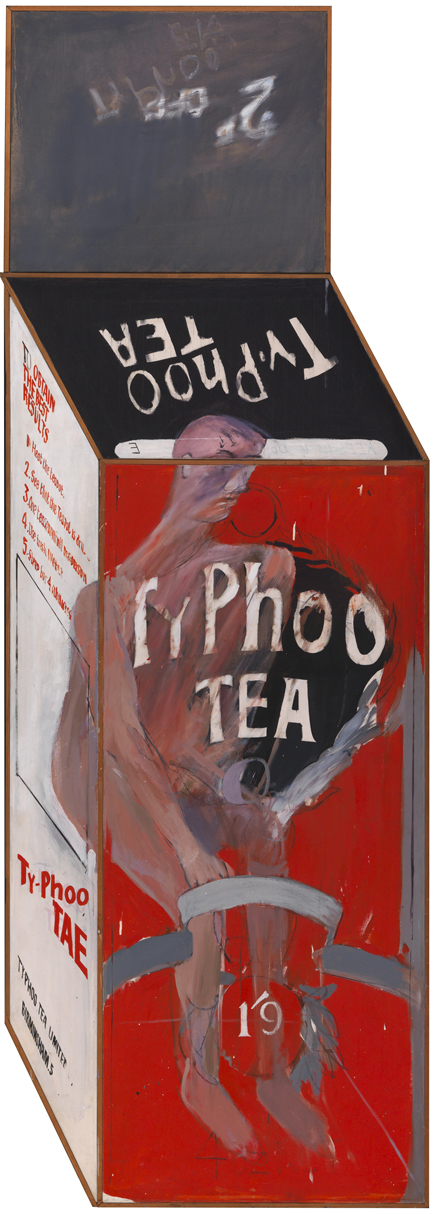

Pop Art

References to contemporary visual culture are the focus of a select group of students at the RCA. The decision to adopt non-fine art elements—for example, bright color, or, in Hockney’s case, graffiti-like scrawls—draws the disapproval of tutors but the enthusiasm of critics, who identify a new [NESTED]movement: Pop Art. (Hockney will never adopt the term for his own work.) Students invite Richard Hamilton to the RCA as a visiting artist, and he provides relief from the tutor’s mounting hostility. At his recommendation, both Hockney and R. B. Kitaj receive awards of merit.

[Richard Hamilton] gave a prize to Ron and a prize to me, and from that moment the college never said a word to me about my work being awful …. Richard had come along to the college and seen what people were really doing, and recognized it instantly as something interesting …. Richard was quite a boost for students; we felt, oh, it is right what I’m doing, it is an interesting thing and I should do it.

Exhibitions

Group

- Annual Exhibition, RBA Galleries, London, UK (Jan 15–Feb 5); catalogue.

- Young Contemporaries, RBA Galleries, London, UK (Mar–Apr 1960); catalogue.