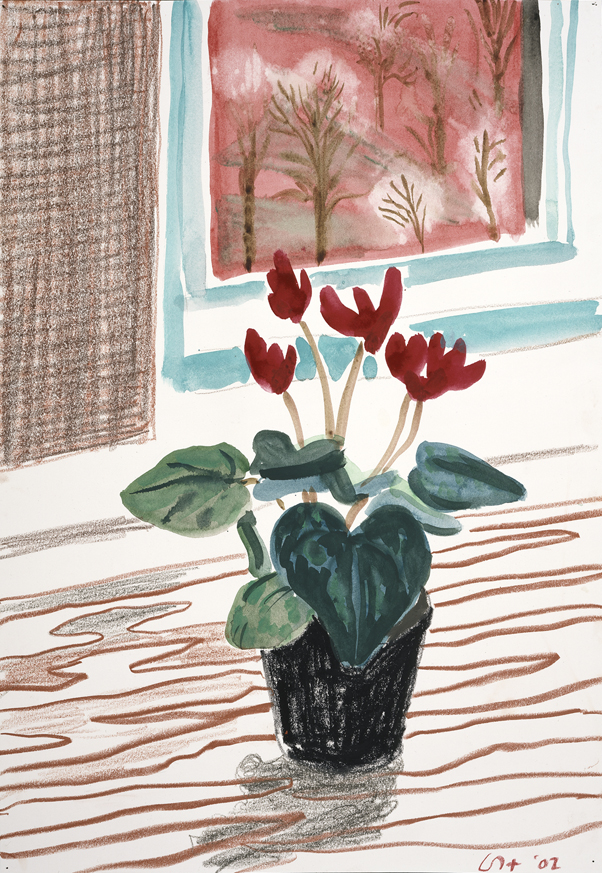

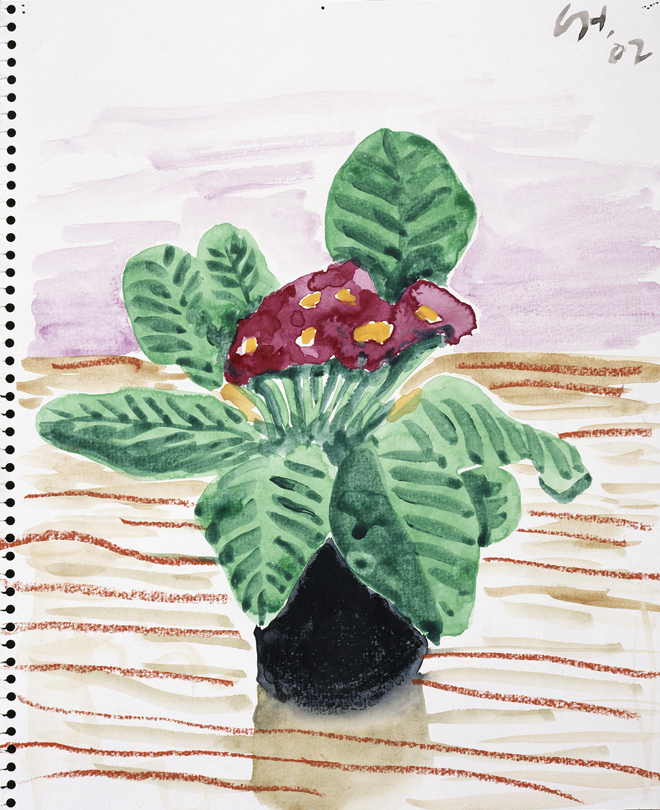

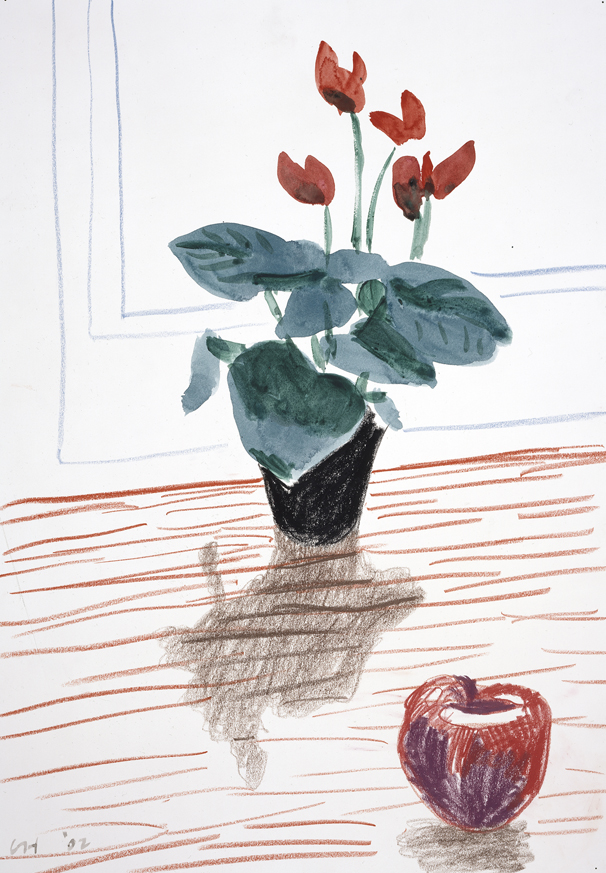

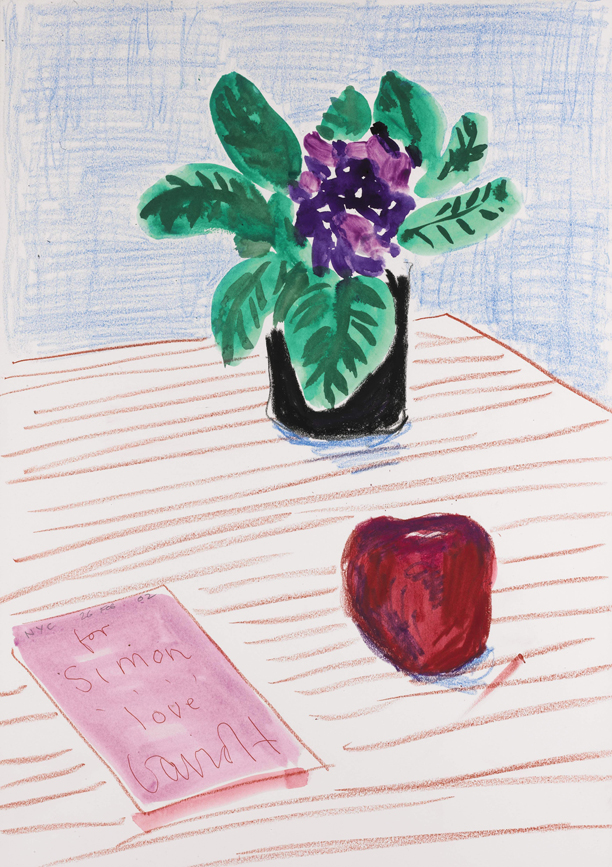

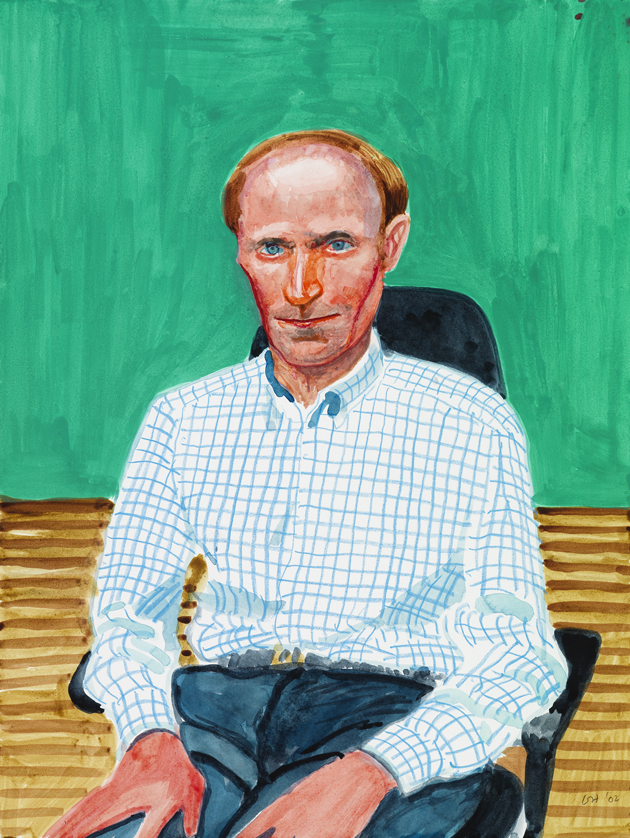

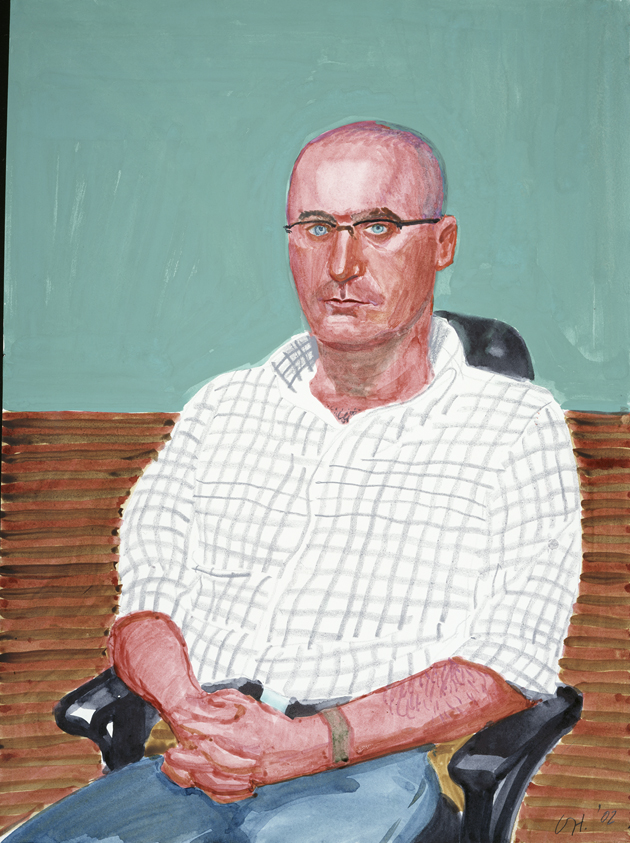

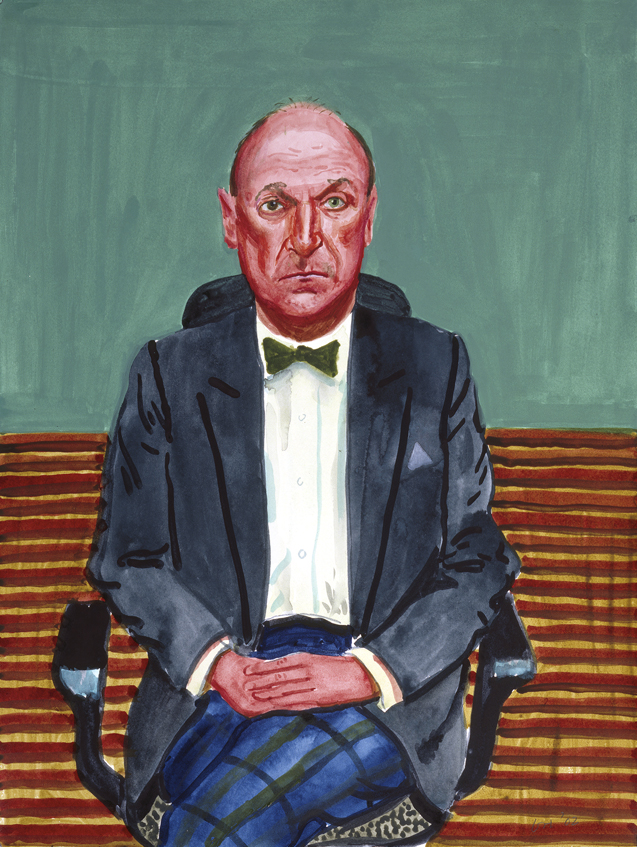

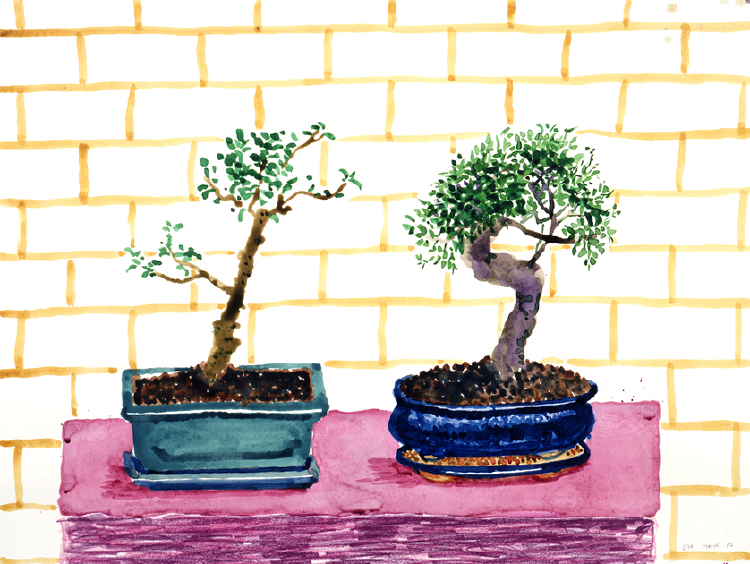

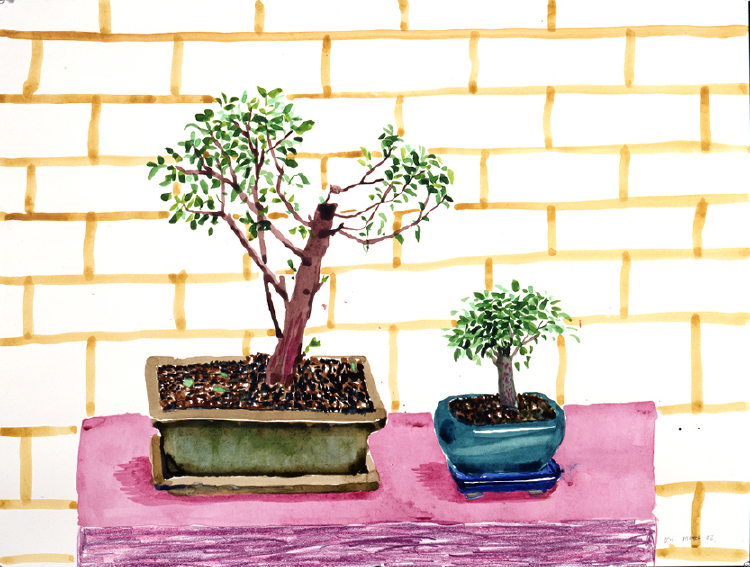

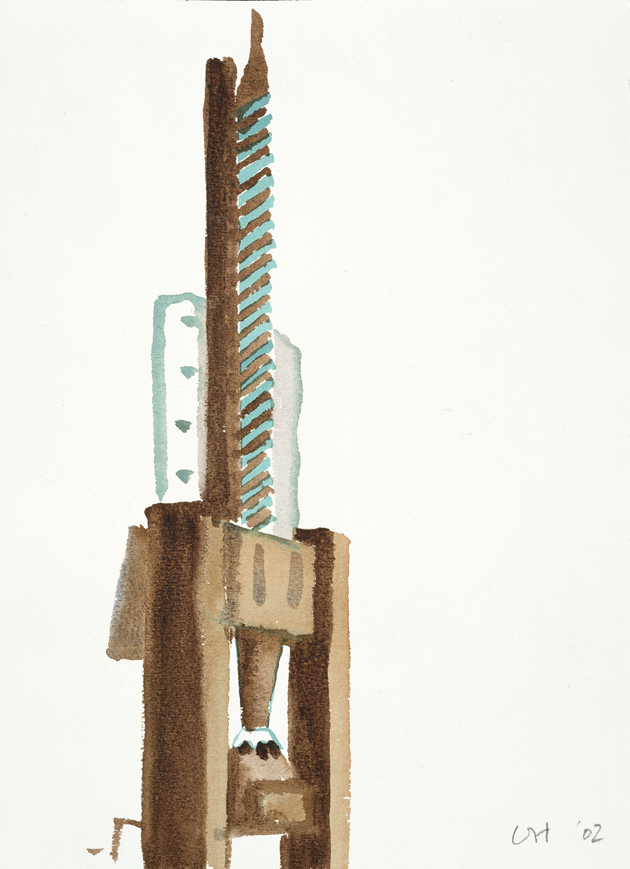

Watercolor

Hockney is in New York for the twentieth-anniversary revival of his production design for the triple bill, Parade, at the Metropolitan Opera. [NESTED]While staying at the Mayflower Hotel, he is inspired by an exhibition of Chinese watercolors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he starts making watercolors, asking friends to sit for single- and double-portraits, and painting still-lifes as well as the view from his room.

I used watercolor because I wanted a flow from my hand, partly because of what I had learned of the Chinese attitude to painting. They say you need three things for paintings: the hand, the eye, and the heart. Two won’t do. A good eye and heart is not enough; neither is a good hand and eye. I thought that was very, very good. So I took up watercolor, which I had not used much before.

It’s the most direct method of laying in a mark .... Oil painting in a sense you have to push. Watercolor just flows .... The thing is it does take a while to master the techniques—having to work, say, from light to dark, because unlike with oils you won’t be able subsequently to daub a light color over a dark one. Everything has to be thought out in advance—and I realized it would take time to master all this. I had to ask myself, was I going to be willing to take six months to learn all this? Well I was, and I did, and it took even longer, mastering the medium, innovating new techniques, but by the end I’d broken into this looser, more immediate way.

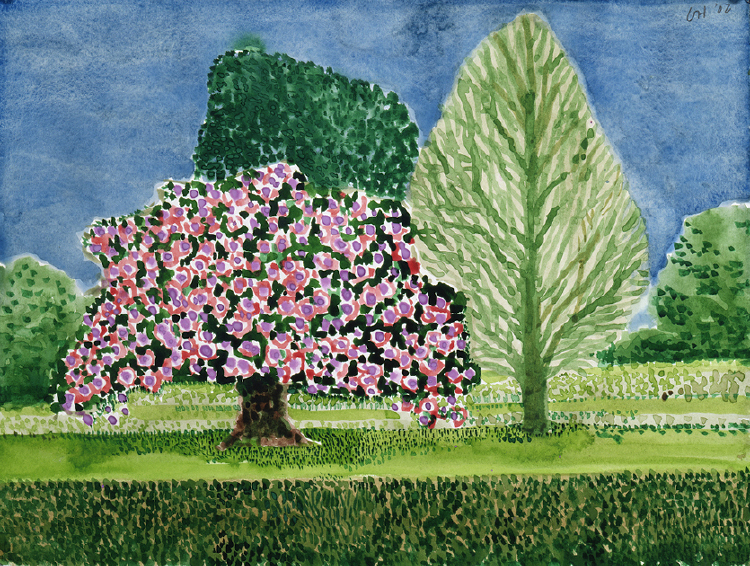

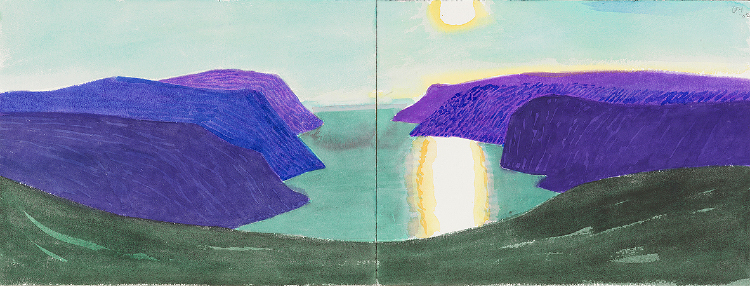

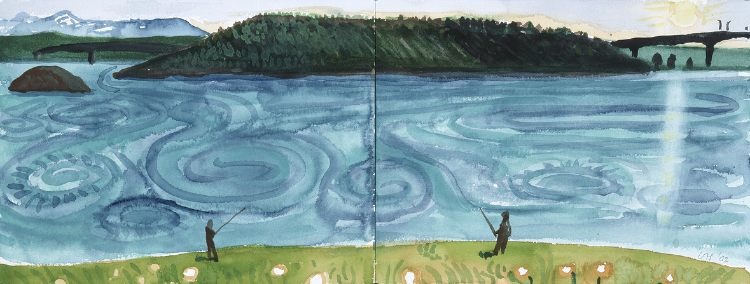

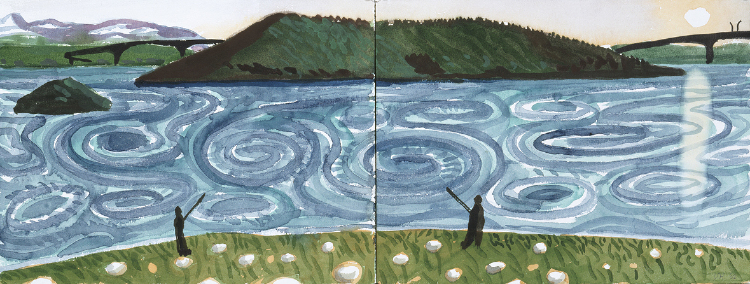

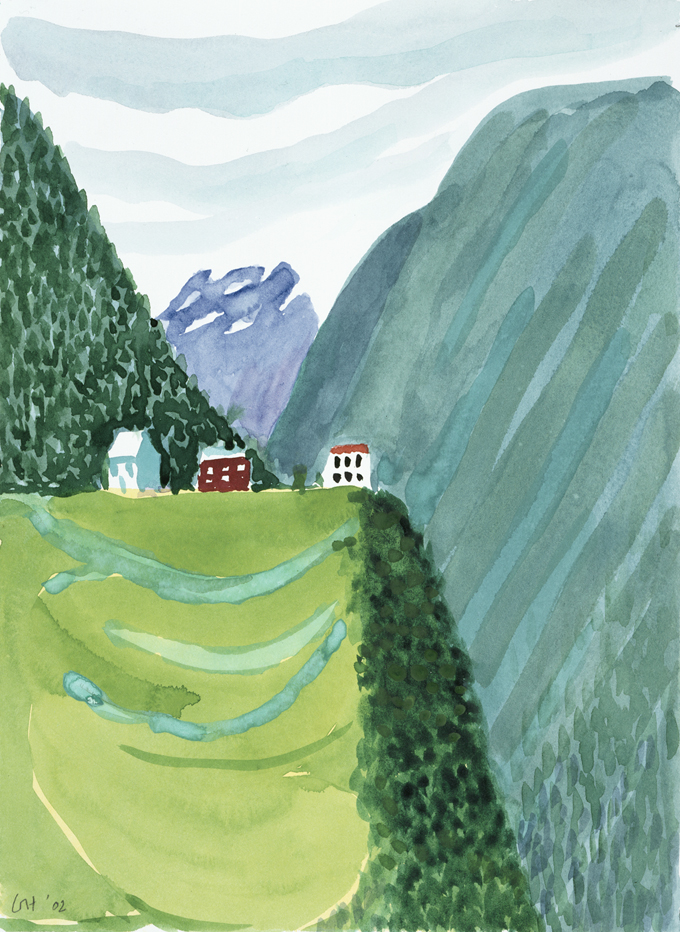

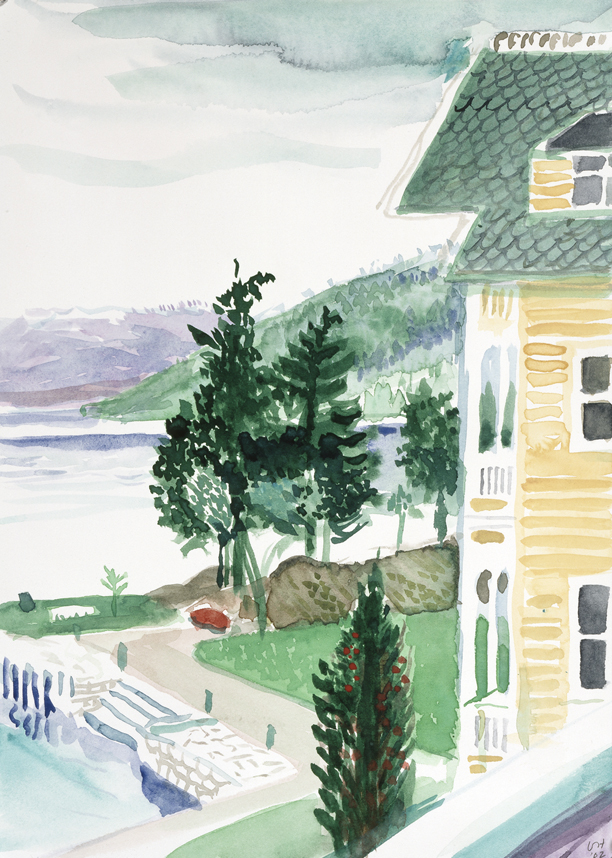

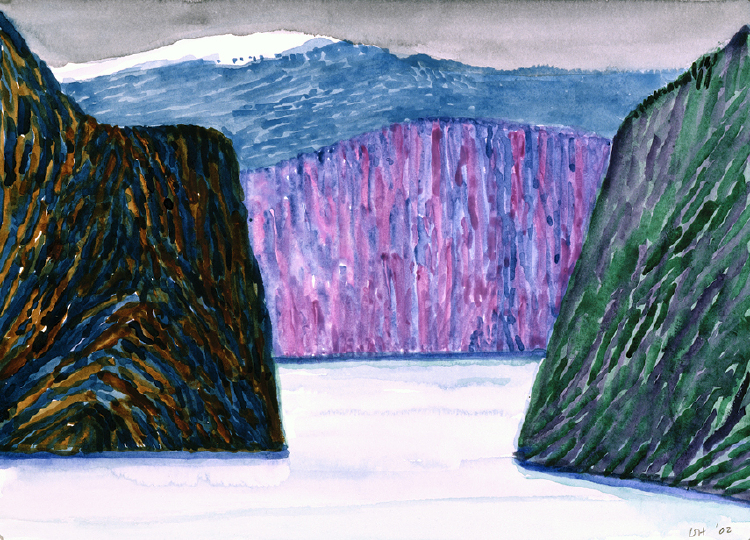

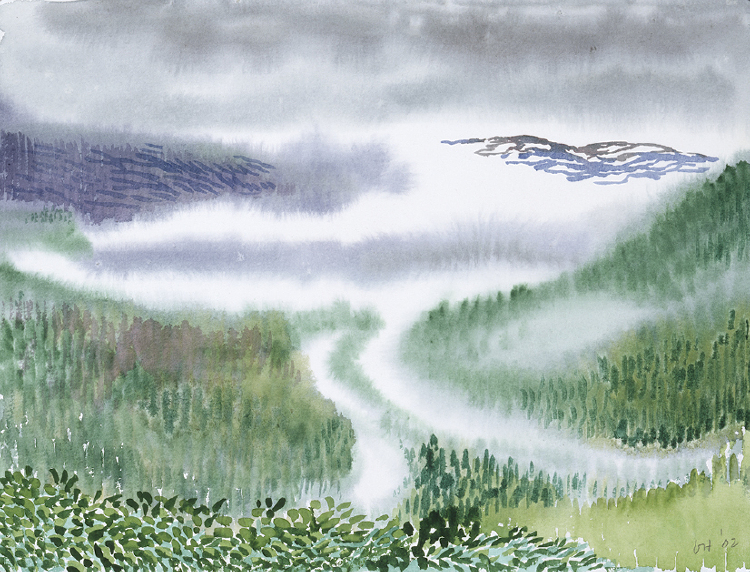

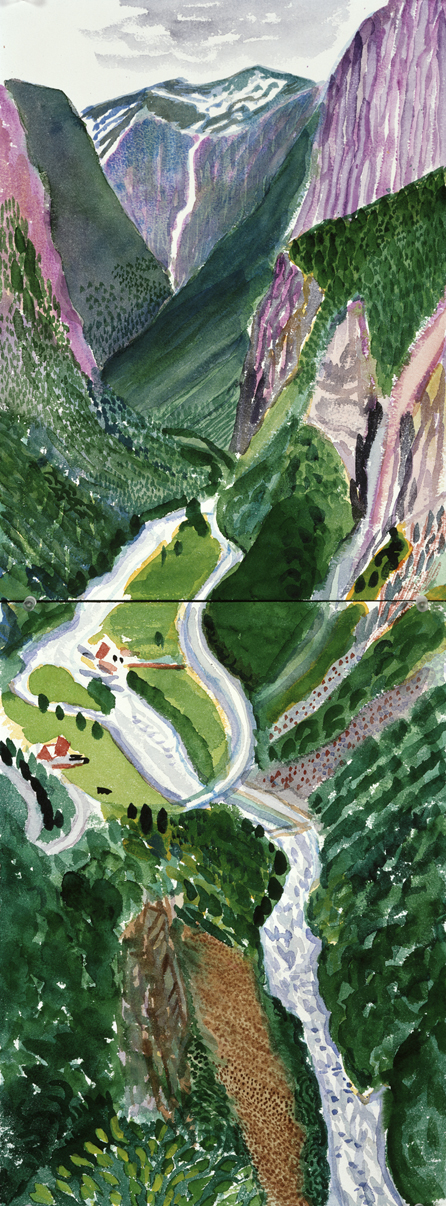

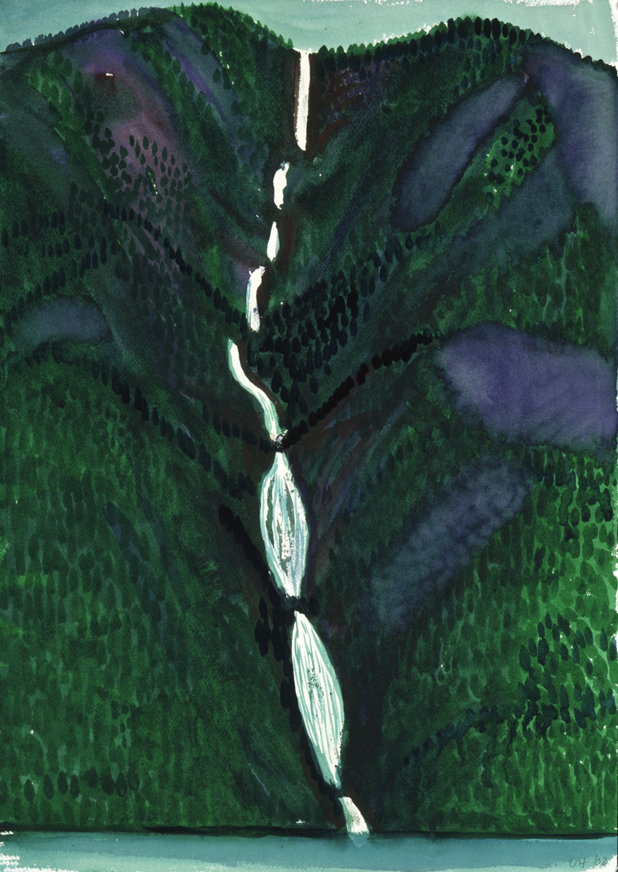

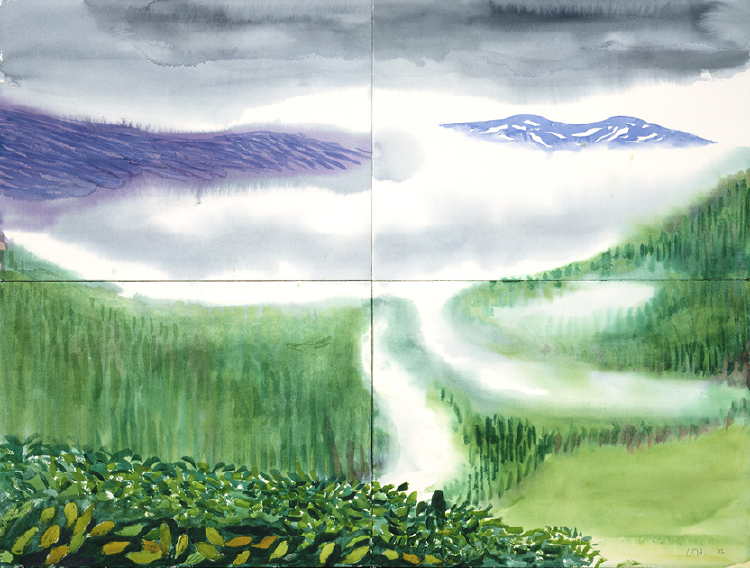

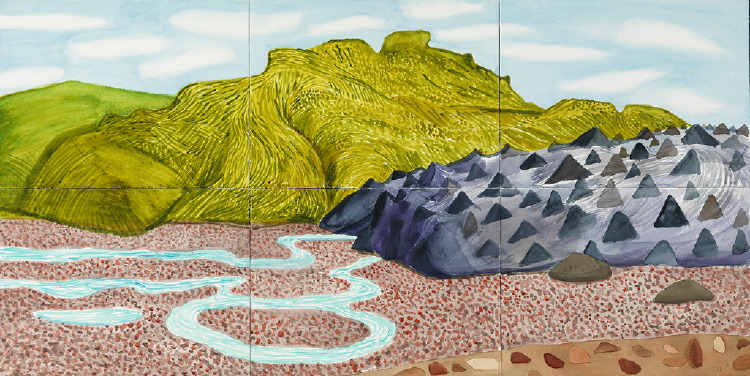

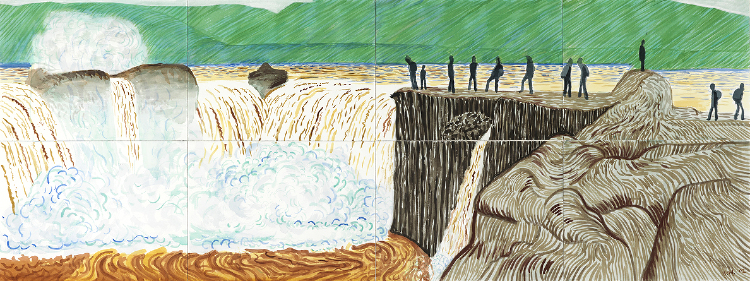

Norwegian fjords and Iceland

His avid production in this medium, at small scale or across several large sheets of paper, carries over into trips to the Norwegian fjords and Iceland, where Hockney is particularly enraptured by the light of the long days of late spring and summer.

To have longer periods of twilight (when color is not bleached but extremely rich) one has to go north. I made a trip to Norway in May, was very taken in with the dramatic landscape and returned to go much further north, when in June the sun never sets at all. You can see the landscape at all hours, 24 hours a day. There is no night. I found myself deeply attracted to it, and then went to Iceland twice to tour the island.

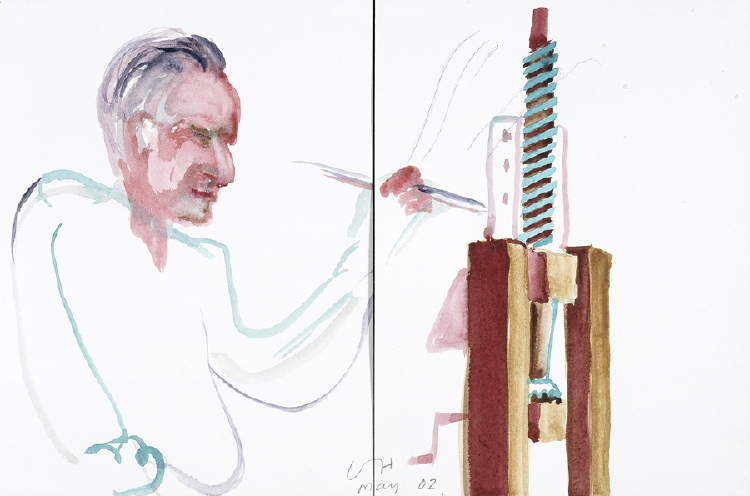

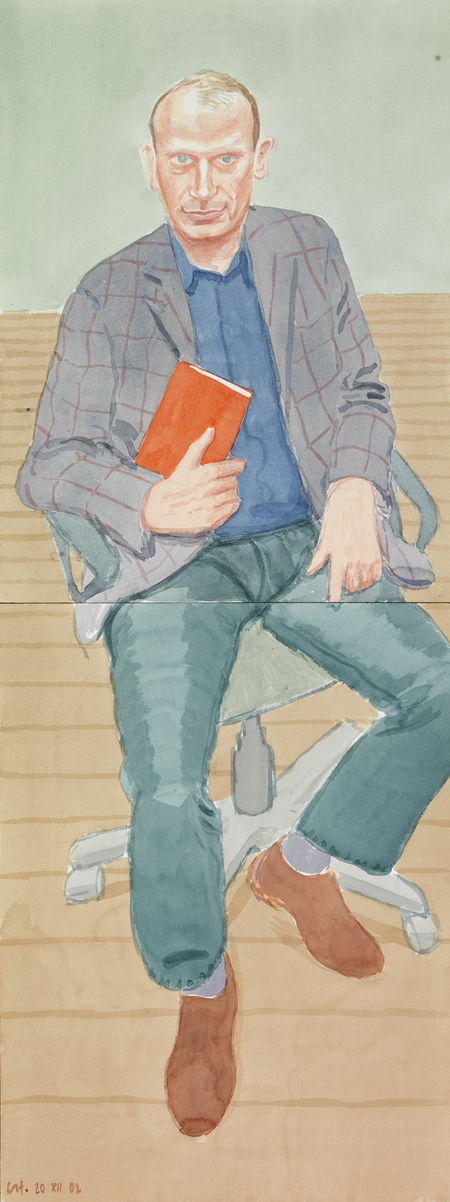

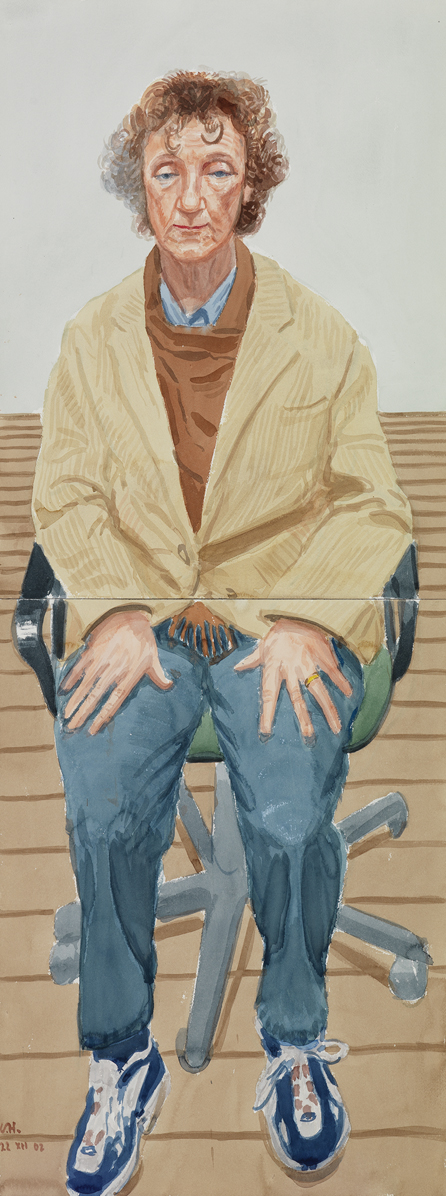

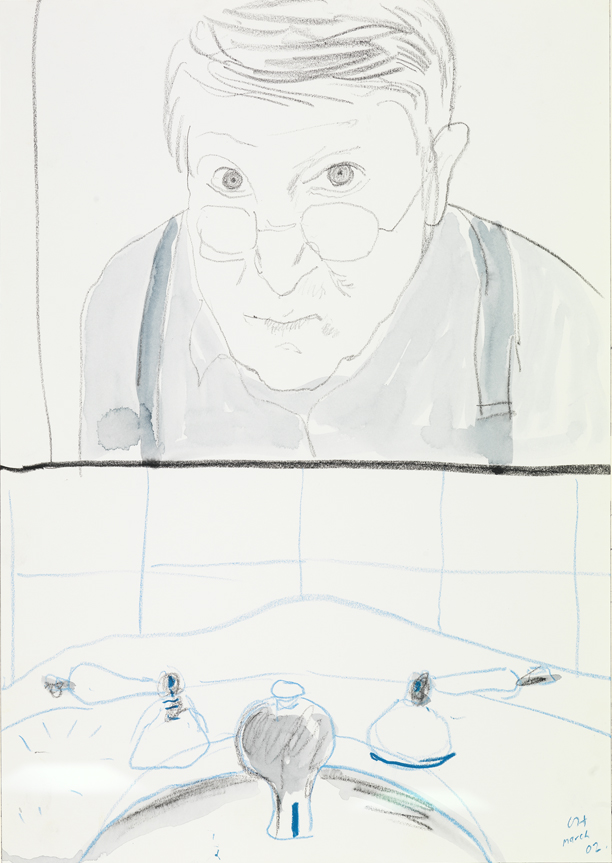

Lucian Freud and David Hockney

Lucian Freud (British, 1922-2011) and Hockney, mutually esteemed peers as portrait painters despite their differences in style, agree to sit for one [NESTED]another. The fruitful exchange is mildly fraught for Hockney in terms of the time investment required for Freud to complete a painting.

I sat for 120 hours for Lucian; he would only sit for three hours for me. He wouldn’t co-operate, really, too restless. The difference between us is, Lucian is shy and I’m a chatterbox, except when I’m painting. I don’t let people talk when I paint. Well, I don’t mind people talking, but I don’t answer back because I’m tuned out. Lips moving are very hard to get. Actually, Lucian and I talked quite a lot when he was painting me. He let me smoke, too, but only if I didn’t tell Kate Moss, who was also sitting for him and who also smokes.

At the Royal Academy with the Queen

Her Majesty the Queen and Hockney present an annual visual arts award to a student at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, while also celebrating the occasion of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee year.

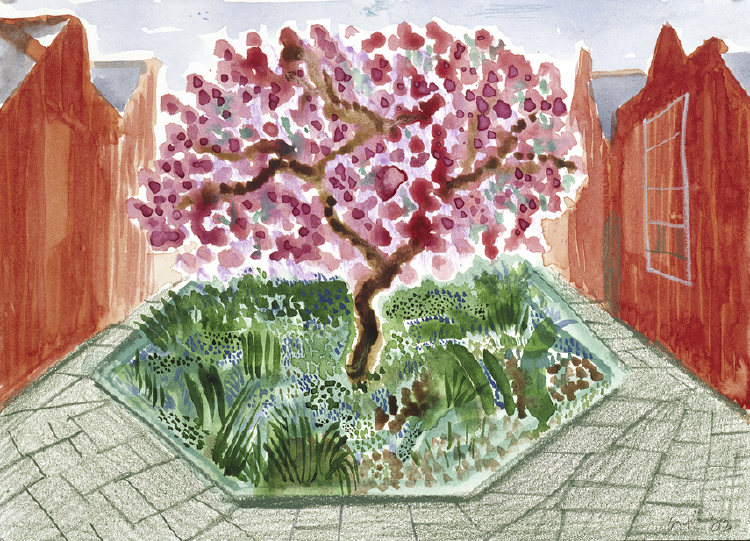

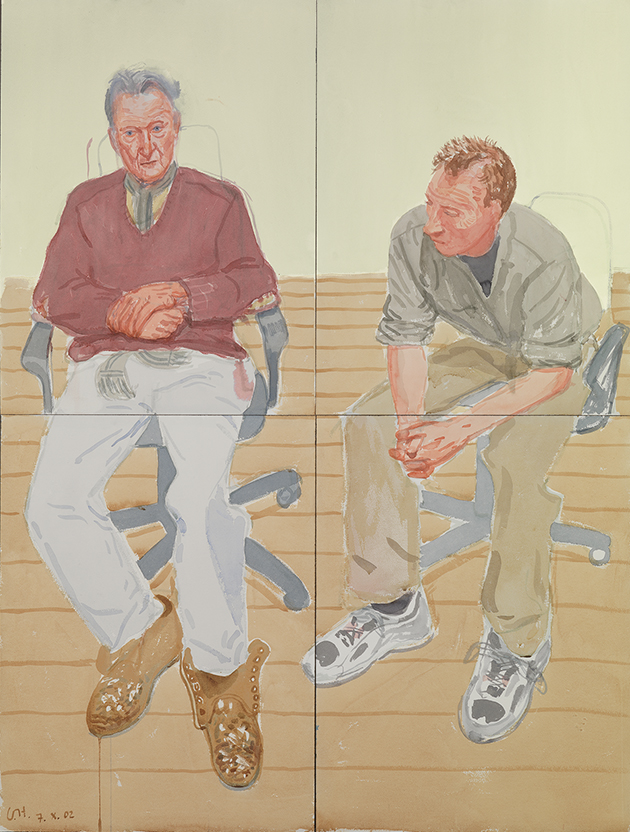

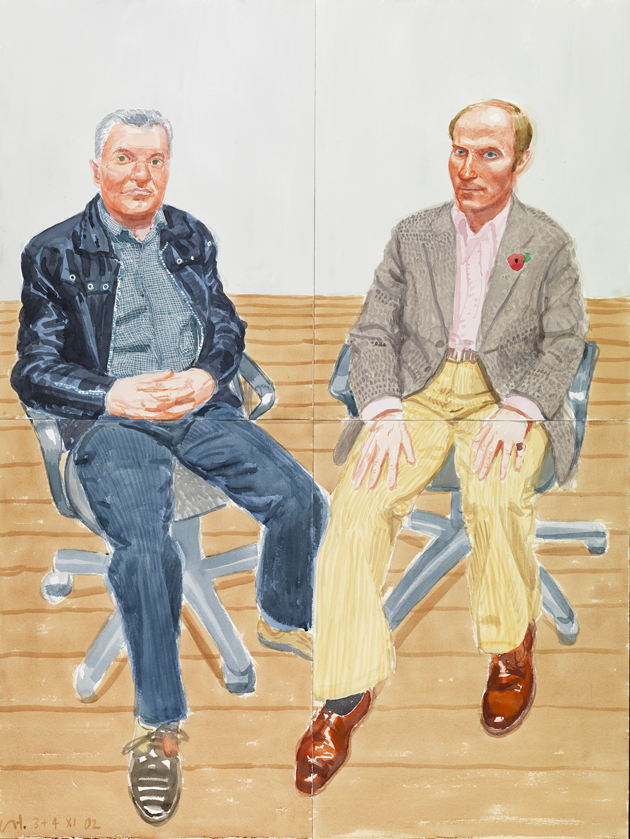

Couples

Commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery in London to paint a double portrait of his friends Sir George and Mary Christie, who organized[NESTED] the Glydenbourne Opera for decades, Hockney decides to capture the couple in watercolor, across four large sheets of paper. This instigates the production of more portraits of this type in the studio, and one double-portrait of a very different nature: a version of Masaccio’s early Renaissance fresco Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1425), which shows Adam and Eve lamenting their newly realized nakedness. Religious subject matter is not typical for Hockney, and, indeed, it is Paradise as a setting that challenges him to depict the narrative.

Two people have something and there is a story. It’s bound to happen. Each couple have some relationship, man and wife, brother and sister, gay lovers, two brothers. I mean any couple is interesting.

The American painter Thomas Cole made a version of this subject in 1827, which I saw in the American Sublime show at the Tate Gallery. It was bombastic, even operatic, with the figures very small. What did the Garden of Eden look like? That seemed to me an interesting visual problem. The subject is, of course, the only real subject. Here Adam and Eve are leaving Paradise, where there is no perspective, no shadows, and no measurements.

Exhibitions

Solo

- Egyptian Journeys, Palace of Arts, Cairo, Egypt (Jan 16–Feb 16); catalogue.

- Prints 1973–1998, Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo, Japan (Feb 12–Mar 16).

- Stage Works, Richard Gray Gallery, New York, NY, USA (Feb 19–Mar 30), travels to Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago (May 4–Jun 29).

Group

- Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK (Jun 7–Aug 19).

- British Artists–Works on Paper 1956-1971: Modern Art Collection of José de Azeredo Perdigão/Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Casa de Cerca, Centro de Arte Contemporânea, Almada, Portugal (Sep 28–Dec 15).

- The Art of Collaboration: The Big Americans, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia (Oct 4, 2002–Jan 27, 2003); catalogue.

- André Emmerich: A Documentary Portrait, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, New York, NY, USA (Oct 10, 2002–Jan 10, 2003).

Publications

Publications

- David Hockney: Egyptian Journeys, by Marco Livingstone, Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.